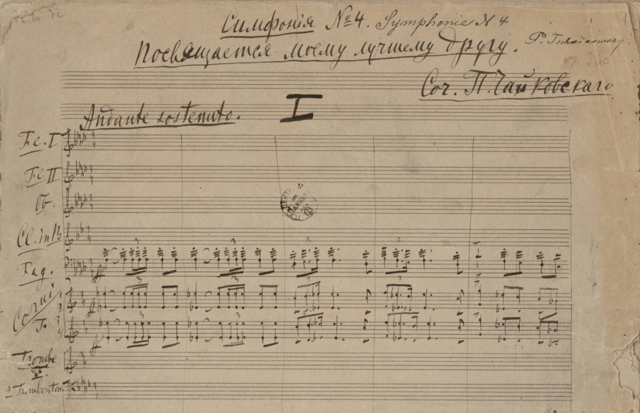

(Originally appeared on the Boston Music Intelligencer, 2/19/18)

"There is not a single line in this Symphony that I have not felt in my whole being and that has not been a true echo of the soul."

- P.I. Tchaikovsky

Benjamin Zander and the Boston Philharmonic in performance.

In every recording of the Tchaikovsky 4th Symphony, when you come to the Trio section of the Third movement, you will hear a piccolo player playing a very fast passage which is not what the composer intended.

The reason for this universal musical mistake is very simple. Tchaikovsky was wandering anxiously from one Italian town to another, trying to banish the demons of his unconsummated 6-week marriage and an apparent suicide attempt, while working at completing his symphony. He reported in a letter from San Remo to his benefactress Mme. von Meck his search for a metronome during his travels*; this evidently failed, and he was forced to send the completed score to the publisher without accurate tempi indications, though he liberally peppered his Fifth and Sixth symphonies with metronome marks—no fewer than 18 in the slow movement of the Fifth alone!

|

|

Thursday, 2/22 at 7.30 pmSaturday, 2/24 at 8 pm (talk at 6:45)Sunday at 3 pm (talk at 1:45) |

Had Tchaikovsky included metronome marks, generations of conductors would not have forced piccolo (and clarinet) players to "recompose" the passage. Could Tchaikovsky, that most meticulous of composers, have written something unplayable?

The third movement is marked Scherzo, Allegro. Its pizzicato perpetuo character has understandably led conductors to assume that the movement is a show piece for virtuoso pizzicatists.

The normal tempo ranges between 69 and 80 to the bar (e.g. Szell with the London Symphony). Maazel with Chicago tops them all astonishingly at 84, which means that every eighth note is going at 336. That works fine for the first part since there are only eighth notes being played – and orchestras are, of course, only too happy to show off their pizzicato prowess.

For the next section, Tchaikovsky marks the tempo Meno mosso. This is usually taken at about 1/4 = 96 or 100 (or 50 to the bar), which gives time for the winds to play four 32nd notes followed by two 16ths in a single beat.

But what happens next is the problem. It returns to Tempo primo with the sprightly brasses leading the way. Even at the slowest of the usual tempos, it is impossible to play four 32nd notes in the time of a single eighth note.

Put your metronome at, say, 74, double it to 148, and then double that to 296. Now imagine playing 4 notes going at twice that speed.

No one can actually do that, though piccolo players the-world-over strain to try. At this breakneck tempo, they must unfortunately change the clear and characteristic rhythm of an 1/8th and two 16ths in order to squish six notes into the time of a quarter note, after which follow a spray of 16th notes, played so fast that they sound like rat-a-tat machine gun fire; it is virtually impossible for all of them to speak clearly.

Here is Maazel's performance of that moment:

Did Tchaikovsky really intend this?He wrote a charming description of his symphony to Mme. von Meck, in which his description of the third movement hardly fits this image at all.

“There is no determined feeling, no exact expression in the third movement. Here are capricious arabesques, vague figures which slip into the imagination when one has taken wine and is slightly intoxicated. Suddenly there rushes into the imagination the picture of a drunken peasant and a gutter song.

Military music is heard passing in the distance. There are disconnected pictures, which come and go in the brain of the sleeper. They have nothing to do with reality; they are unintelligible, bizarre.”

Suddenly all is clear! First the winds sing the song of the drunken peasant together (meno mosso) and then the military music strikes up (pp) in the far distance (Tempo primo). The military band, even a Russian one in a dream, would be expected to march at traditional Sousa march tempo MM = 120-126, rather than the usual tempo for this section of MM = 138-160.

The drunken clarinet, tipsy, gay and relaxed, has just enough time to negotiate the four very quick 32nds followed by two clearly articulated 16ths —all in the time of one quarter and the piccolo player might actually manage a gleeful smile as she tosses off her playful roulade—exactly as Tchaikovsky composed it.

Thus, the entire movement is transformed from a frantic virtuoso show-piece that cannot actually be played correctly by even the greatest virtuosi, into a delightful interplay of “capricious arabesques…vague...slightly intoxicated figures.” Brass bands play so softly that they appear to be in the distance; along with a drunken peasant or two – all merging in a dream.

One looks in vain for a performance of Tchaikovsky’s symphony that conveys what the composer meant in this section. This weekend the Boston Philharmonic, with piccolo player Sarah Brady proposes just that.

I venture that there are many other misunderstandings of this warhorse.

For instance, Tchaikovsky’s description of the Finale is very far from the crass, ovation-grabbing, bombastic bluster of tradition. Russian conductors in particular, all seem to agree that it should be played prestissimo (Mravinsky’s notorious rendition has become a YouTube meme), though Tchaikovsky marks it only Allegro con fuoco, not Presto.

Mravinsky's performance of the end of the Finale:

In the absence of the all-important metronome indication, perhaps Tchaikovsky’s touching description will be sufficient to set us right:

"As to the finale, if you find no pleasure in yourself, look about you. Go to the people. See how they can enjoy life and give themselves up entirely to festivity. The picture of a folk holiday. Hardly have we had time to forget ourselves in the happiness of others when indefatigable Fate reminds us once more of its presence. The other children of men are not concerned with us. How merry and glad they all are. All their feelings are so inconsequential, so simple. And do you still say that all the world is immersed in sorrow? There still is happiness, simple, naive happiness. Rejoice in the happiness of others — and you can still live."

What audiences at the bpo concerts will hear (probably for the first time) is a festive movement full of joy and happiness at a tempo 30 points on the metronome slower than Mvravinsky's rush to the inevitable standing ovation. Thank goodness we have the description of his true intentions in the precious letter to Mme. von Meck!

*“A few more days were devoted to putting the final touches to the full score, which I shall take with me, so that in Milan I might obtain a metronome and insert the correct tempi”.

*Letter from San Remo 26th December 1877

.jpeg?width=100&height=100&name=Zander%20Headshot%20(Email).jpeg)