Whatever is said in the effort to describe any great musical work, one has the feeling that one is talking

Whatever is said in the effort to describe any great musical work, one has the feeling that one is talking

Mahler understood this, and although he wrestled with the idea of writing 'programs' for his symphonies he came to deplore program notes—not only as a distraction but also as a disruption of the listener's experience.

Words, as Mendelssohn said, are far less precise than music, and so the words one uses to describe a piece will always express the emotions conveyed by the piece less precisely than the piece itself. Yet here is what Alban Berg wrote about Mahler's Ninth:

"The whole [first] movement is permeated with the premonition of death... Again and again it crops up; all the elements of terrestrial dreaming culminate in it...most potently, of course, in the colossal passage [bar 308] where premonition becomes certainty—where in the midst of the highest power of almost painful joy in life, death itself is announced 'with greatest force'."

When an artist like Berg speaks in this way, who can question the appropriateness of at least attempting to make such observations? After all, a few pages after the section that Berg describes, Mahler himself writes in the score, over one of the most devastating and ominous passages in all music, the words "Wie

We must recall that Mahler lived at a time when art was manifestly personal. The years before the First World War were years of profound unrest in which a sense of dread and exhaustion permeated Europe, eliciting the paintings of Klimt, Beckmann and Kokoschka, the writings of Krauss, Wedekind

It is essential, then, that we allow ourselves to experience Mahler's Ninth in emotional terms—not merely as a self-indulgence, but because it is precisely in emotional terms that the work unfolds structurally. The listener inevitably has great difficulty in grasping the structure of the first movement. Is it in sonata form? Well, it is—but I cannot say that this form can be more than dimly apprehended over the thirty-minute span of its length. For if one tries to analyze the movement in terms of traditional sonata structure, one becomes quickly confused. When the second theme—if that is what it is—enters at bar 29, it is not in the dominant, as we should expect, but rather in the tonic minor: and it is immediately followed by a restatement of the main theme in the tonic!

Is this, after all, a rondo? In fact, the movement keeps returning to the main theme and then veering off again into what sounds like the Development. Thus while sonata form is certainly the background principle of the movement, it is virtually impossible to keep any sense of location while the music is being experienced dramatically. Even the critics disagree about where the Development, Recapitulation

There seem to be two kinds of music in the first movement: music that is gentle, harmonious, sublimely beautiful, and resolved; and music that is complex, dissonant, full of tension, and unresolved. And the structure of the movement seems to set these two kinds of music against each other. The former kind may be said to represent hope, joy, the possibility of peace, spiritual meaning, and an acceptance of death, while the latter may be said to represent hate, anguish, suffering, doubt, confusion

Musically speaking, the former is presented in the ardent, yearning, nostalgic harmonies of late-nineteenth-century Romantic style; the latter, in the tortured, involuted, contrapuntal, and often virtually atonal style of the early

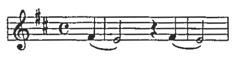

Seen in these terms, the structure is much easier to grasp. The first movement opens tentatively, expectant and yet sparse in a way that prefigures the style of Webern. Perhaps it conjures up images of the beginning of the world, though this opening, unlike that of Mahler's First Symphony with its sounds of awakening nature, is full of foreboding: the primal

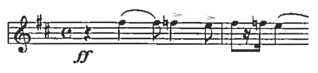

But all too soon this peace is disturbed, by the up-thrusting, dissonant melody in the first violins and by the bitter, syncopated trumpet motive.

This motive permeates the whole

Periodically, the music moves back towards D major and the nostalgic second-violin melody, as if trying to resolve the conflict and recreate the peace of the opening; but every attempt is foiled, and each time the music veers off again into turmoil and dissonance. Each wrenching-away is more violent and more dissonant than the preceding one, just as each return to D major is a little more confident and prolonged. In the end—after the passage beginning at bar 308 that Berg indicated—the syncopated trumpet motive is finally tamed and transformed into the lovely D-major horn duet, with its gently undulating harp accompaniment.

If we hadn't realized it before, it may now be clear that the two contrasting "themes" that encapsulate the two opposed types of music in this movement, the nostalgic D-major second-violin melody

and

and

They represent two aspects of the same dilemma—despair is an inevitable accompaniment of hope and love—and they are finally resolved in the horn melody, which combines elements of each and takes us beyond both into a sublime reconciliation, a glimpse of bliss at the very end of the movement.

This technique of thematic variation or transformation is one of the basic compositional modes of the Ninth, and Mahler's use of the technique is one of the things that makes this symphony a crucial work in the history of music. By this time, in fact, Mahler is hardly writing themes or melodies at all. Rather, his music is composed with motives, as are Beethoven's late quartets and, more significantly, the early works of Schoenberg—for example the Five Pieces for Orchestra, Op.16 (1909), which Mahler especially admired. To be sure, there are melodies in the Ninth. But they are constantly being transformed into one another; the basic motives are so freed from their melodic roots that each can repeatedly be made to form new melodies, which often differ in shape and character from the earlier ones.

Also, just as in Schoenberg, there is almost complete independence among the voices. In most eighteenth-century and nineteenth-century music, even in Brahms's most complex polyphony, there is usually a melody and an accompaniment, a hierarchy of importance among the voices. But in the first movement of Mahler's Ninth, especially in the sections depicting despair and chaos, there are virtually no subservient voices. What

With often as many as ten or eleven different voices to be heard at once, and with Mahler's painstakingly precise indications of phrasing and dynamics for each voice, often different from those for all the other voices, the Ninth makes extraordinary demands on even the ablest orchestral players. Orchestral players are trained to play with one another, to blend their sonorities and dynamics into a balanced whole. They are discouraged from projecting their own characters and personalities. But in this music that will not do; the players must be encouraged not to compromise the sharp oppositions, nor minimize the strangeness, even the ugliness that Mahler has written into his score.

BPYO performing Mahler's 6th Symphony in Symphony Hall, 2017. [photo credit: Paul Marotta]

This is why Mahler's music, and especially the Ninth Symphony, needs so much care in its preparation. By modern

The overall form of the Ninth, with two huge slow movements flanking the two large scherzi in the middle, is most unusual and presents its own problems. But I am convinced that it works—indeed, that it had to be as it is, given the content of the music.

In the traditional symphonic scheme, the first movement is dense, intellectual, and highly structured, with a slow movement, a light scherzo, and a brilliant finale following to provide welcome relief. But in Mahler's

So the "victories" won in the first movement have to be tested. That Mahler does so in two middle movements of such immense size and density is a measure of the dimensions of the struggle. These two movements are in fact so large and so complex, their energy so relentless, that they threaten to overbalance the structure of the whole work. But in the end they don't; in

And it is hard-earned not only for the composer but also for the players and the audience. In fact, the length and difficulty of Mahler's Ninth are in themselves elements of one's experience of the work. Any orchestra that found Mahler's Ninth easy, or any audience that was not overwhelmed by its length and complexity, would have missed the whole point. The struggle just to play the notes correctly, to sort out the complex rhythms, to realize in performances the intricate instructions that appear on every page, to render audible in their proper relation to one another all the various lines of the music—this is central to the experience of Mahler's Ninth. It must never be made to sound easy or glib or even comfortable.

In the second

Aside from the energy, the most amazing thing about the third movement—which Mahler marks Rondo Burleske—is its contrapuntal mastery. At

The music of the fourth movement is not joyful or triumphant—Mahler has slipped from the radiant D major of the opening movement to a dark, somber D-flat major—but the textures are rich and full, the counterpoint astonishingly opulent. True, the climaxes are never fulfilled and there are moments of extreme withdrawal—those bleak, passionless passages that Mahler marks to be played "

We seem to emerge from contemplating the reality of death not in a state of gloom, but with a sense of joy. Unlike Tchaikovsky's Pathétique, a model for this symphony, it ends in major

Part of the reason the end is so moving is precisely

"What one makes music from is still the whole—that is the feeling, thinking, breathing, suffering, human being," wrote Mahler to Bruno Walter. If we didn't know that Mahler faced imminent death, we would still know that the music could not have been written except by one who is facing the ultimate test.

"What one makes music from is still the whole—that is the feeling, thinking, breathing, suffering, human being," wrote Mahler to Bruno Walter. If we didn't know that Mahler faced imminent death, we would still know that the music could not have been written except by one who is facing the ultimate test.

But the silence at the end is not the silence of death

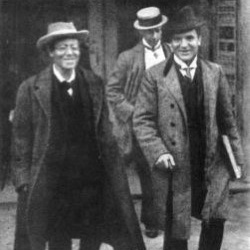

Mahler & Bruno Walter. 1908

.jpeg?width=100&height=100&name=Zander%20Headshot%20(Email).jpeg)