Rachmaninoff wrote the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini between 3 July and 18 August 1934. The first performance was given on 7 November 1934 in Baltimore, Maryland, with the composer as soloist and Leopold Stokowski conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra.

Solo piano, two flutes and piccolo, two oboes and English horn, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, snare drum, triangle, bass drum, glockenspiel, harp, and strings.

Audiences everywhere instantly took to the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, and it quickly became an indispensable repertory piece. Among connoisseurs and professionals it is probably the most admired of Rachmaninoff’s works. It embodies his late style at its brilliant and witty best, it has one of the world’s most irresistible melodies, and it gives audiences the satisfaction of watching a pianist work very hard and with obviously rewarding results. Moreover, variation form, which is what we have here, though disguised by the title Rhapsody, is an unobtrusively effective corset, useful because control of large designs had never been the most highly developed among Rachmaninoff’s remarkable gifts. The composition of the Variations on a Theme by Corelli three years earlier had no doubt been profitable preparation for the Rhapsody.

Turning to Paganini’s Caprice No. 24, Rachmaninoff was following in the footsteps of Schumann, Liszt, and, more particularly, Brahms. I make the distinction because Brahms’s two books of variations are original reflections on the theme, even though they make occasional allusions to Paganini’s own variations (as do Rachmaninoff’s as well), while Schumann’s and Liszt’s studies are not so much independent pieces as pianistic expansions of Paganini’s Caprice.

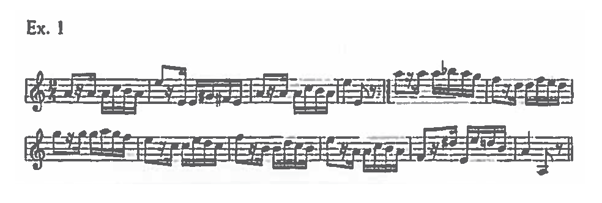

About 1805, while part of the musical household of Princess Elisa Baciocchi, just installed by her brother Napoleon Bonaparte as ruler of the former Republic of Lucca, Paganini codified his evolving technical resources in his Opus 1, but not until 1820. The Caprice No. 24 is a set of eleven variations plus a fifteen-measure “finale” on the now-so-familiar leaping theme with its striking contours and simple, easily grasped harmonic scaffolding.

Rachmaninoff begins with an introduction, which is followed by Variation 1 (marked precedente), the theme itself, Variations 2 through 24, and the coda. What is this about? Rachmaninoff takes the second half of the first measure as his launching pad and, beginning in medias res, uses it over eight measures to guild up excitement and suspense. Then comes Variation 1—on a theme not yet heard. It is a skeleton, appropriate enough for an evocation of the cadaverously thin Paganini, and Rachmanino draws it for us by sounding only the first note of each of Paganini’s measures (he also changes Paganini’s F and E in the sixth and eighth measures to D and C). As this variation nears its close it begins to assume a hint of flesh. Very likely Rachmanino got the idea of variations before a theme from the finale of Beethoven’s Eroica.

The theme proper, when it appears, is assigned—again with a nice sense

of the appropriate—to the violins, while the virtuoso pianist, the translated Paganini, as it were, accompanies with the skeleton. (Here are sixteen measures of a Rachmaninoff concerto that anyone can play!) As in Variation 1, the last measures add new activity, looking ahead a bit to what is to come, a technique Rachmaninoff uses with some consistency throughout the Rhapsody. Unlike Brahms, he has no notion of sticking to the phrase structure and measure count of the theme.

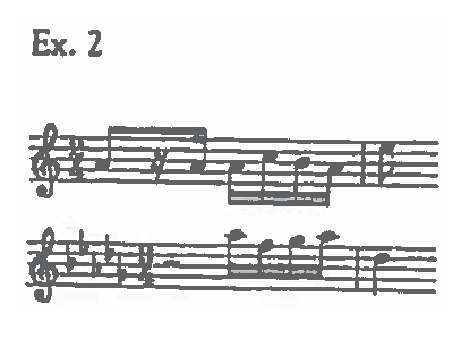

I, in turn, have no notion of writing a variation-by-variation description. Taking the Rhapsody by chapters, this is what we hear: The first five variations are increasingly excited, after which the sixth is more relaxed and even allows time for a couple of mini-cadenzas. Variation 7, rather slower, introduces a new theme, the Dies irae from the Gregorian Mass for the Dead, a melody that haunts so much Romantic music from the Berlioz Symphonie fantastique and which Rachmanino was particularly fond of quoting. While the piano being chastened by the funeral atmosphere, violins being irrepressibly and slyly frivolous. The Dies irae, though always a secondary idea in the scheme of the piece, remains very much a presence. Though Variation 10, Rachmanino is particularly concerned to explore everything that is sinister about Paganini and the Dies irae; his imagination and skill in orchestration play a large role here.

Using Variation 11 as a loose, cadenzalike transition, Rachmaninoff begins a new phase in Variation 12, which is in a demure minuet tempo. The basic allegro is soon resumed, but this chapter is rounded off with another variation (No. 16) in a gentler tempo and scored almost as chamber music. Variation 17 is another transition, but a strange and dark one, with little suggestion of Paganini. The travail of this mysterious exploration – it is like making your way, hands along the wall, through a dark cave – is rewarded when the music emerges into the soft moonlight of D- at major and the inspired melody that Rachmaninoff found by inverting Paganini’s theme. “This one,” he said, “is for my agent.”

Actually Variation 18 is three variations in one, for Rachmaninoff gives us three different continuations of a single beginning, the scoring getting warmer as he goes. He has moved far from where he started, in mood and also in key. The harmonic relationship of Variation 18 to the Rhapsody as a whole is like that of the Adagio of Rachmanino ’s Piano Concerto No. 2 to its first movement – and, for that matter, like the slow movements of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3 and Brahms’s Symphony No. 1 in their contexts. How do you leave such a dream? Rachmaninoff in his concerto and Brahms in his symphony do it by gentle transition, Brahms’s being wonderfully subtle as well; Beethoven does it with a joke. Here Rachmaninoff chooses Beethoven’s example. The orchestra wakes the dreamer – and the rapt audience – with a snappy reminder that our proper business is to be vivacious and in A minor (it is a characteristic touch of wit that the actual wake-up call is a chord of A major), and the piano responds at once with a bravura variation, quasi-pizzicato, and close to Paganini’s own Variation 9 with its dazzling left-hand pizzicatos.

Rachmaninoff’s Variation 19 begins the nal chapter, saturated in Paganiniana and spooky Dies irae atmosphere. At the summit of a hectic climax, one with palpable touches of Broadway, the pianist launches into a brief cadenza with thundering octaves. Somehow this has managed to position itself in A- at major, and, upon resuming with Variation 23, the piano is amused to pretend that it really believes this to be the right key. The orchestra is not amused at all, but it takes two firm interventions to get things back on the proper harmonic course. The two nal variations work up tremendous excitement; the mischievous coda, all two measure of it, is another stroke of delicious wit.