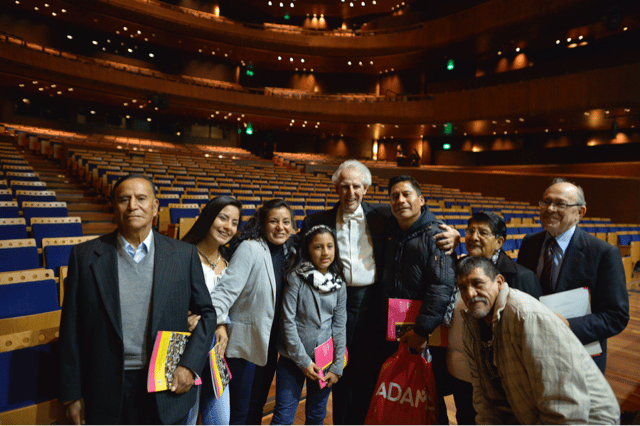

BPYO members celebrate with the audience after a children's concert in Buenos Aires, Argentina

I have lead 22 international youth orchestra tours, but this most recent tour with the BPYO to South America has left a different, and perhaps deeper impression. I hope after reading this chronicle you will understand why.

Let’s begin with the seemingly unreasonable logistics: a tuition–free youth orchestra of 105 players on a concert tour to three countries in South America; 120 people, 34 bus rides; 8 plane trips; interactions with well over 20,000 people; 7 concerts in packed concert halls; and countless side-by-side events with young South American musicians. Nearly perfect behavior and barely a harsh word spoken in 13 days.

That needs some explaining!

Richard Dyer, former Chief Music Critic of the Boston Globe came along as our insightful and eloquent chronicler; his eight blogs tell the story from the perspective of an informed and experienced outsider.

Richard Dyer, former Chief Music Critic of the Boston Globe came along as our insightful and eloquent chronicler; his eight blogs tell the story from the perspective of an informed and experienced outsider.

Paul Marotta, top photographer with Getty Images, captured hundreds of gorgeous photos (shown throughout this blog post). You can view the collection here: Marotta Tour 2017 Photos

Doug Lowe captured on film hours of footage for a TV documentary to be released later in the year.

Doug Lowe captured on film hours of footage for a TV documentary to be released later in the year.

Dave Jamrog recorded and filmed everything.

In this blog I will call on all this, as well as comments from BPYO members culled from their final “white sheets”. Most importantly, in this blog, you will be able to click on and hear recordings of the performances that caused such a sensation in the concert halls and rehearsal rooms of Peru, Argentina and Uruguay.

Let’s Take Day 1...

We arrived in Lima late at night, having gathered at the airport in Boston at 6.30 a.m. and traveled all day.

No one got to bed before 2 a.m. The original plan had been to give everyone the first morning off to recover from the trip, so they would be fresh for the rehearsal in the afternoon and the first public concert that evening.

No one got to bed before 2 a.m. The original plan had been to give everyone the first morning off to recover from the trip, so they would be fresh for the rehearsal in the afternoon and the first public concert that evening.

But at the last moment, it was decided to arrange a side-by-side with the El Sistema–inspired youth orchestra Sinfonia Por el Peru, a program for Melanie Chen, BPYO cellist

deprived kids in Lima sponsored by Telefonica, the main Spanish phone company. I had befriended their President in Madrid a few years before and he had told me how passionately committed the company is to provide this invaluable program throughout South America. The Telefonica executives saw a great opportunity in bringing BPYO and the Lima group together and so made all the arrangements including streaming the whole event back to Spain via satellite. It was a great idea! But what were we supposed to play? How was this going to work? They didn’t play any of our repertoire and we didn’t play any of theirs.

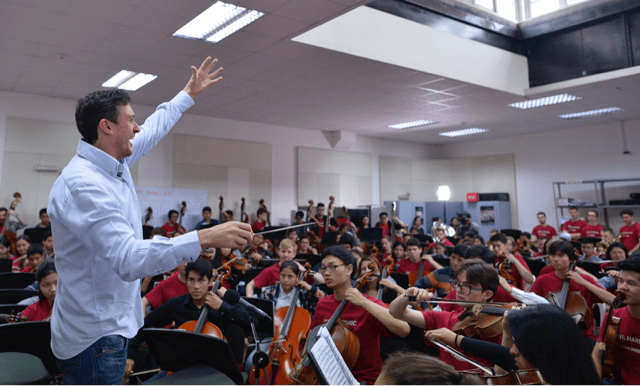

There was barely enough room in the cramped classroom for the more than two hundred musicians and their music stands. They were going to be crammed in like sardines with barely any room to draw their bows.

As 10 o’ clock approached, their conductor still hadn’t appeared and I was trying to pretend that I wasn’t getting increasingly frantic. We still had no idea how we were going to manage things. How was this supposed to work? What should we play? Above all how was this going to look to the Telefonica Execs back in Spain? I was in a classic 'Downward Spiral' mode. “This kind of chaos is really unacceptable”, I muttered under my breath. The assurance that everything in South America always works this way was no help at all.

We decided that as soon as their conductor arrived they would kick off by performing Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture, which they had prepared, and then we would perform Hindemith’s Symphonic Metamorphosis for them and then take it from there. However, once everyone was settled, with a Peruvian and a BPYO musician on each stand, it was obvious that it wouldn’t work. The musicians from each respective orchestra were too far from each other to be able to be in contact.

On a sudden impulse, I announced that everyone should play the 1812 Overture. This was a crazy thing to suggest because it is a difficult piece, especially for the strings, and our players had never played it. It was unreasonable to expect them to play it at sight. It was likely to be an embarrassing mess.

But what happened next was the first “miracle” of the tour. Hugo Carrio, their conductor, walked in with a radiant smile – a smile that hardly left his face for the remainder of the morning! Through a mix of charisma, energy and technical mastery, he took that huge orchestra through a stirring performance of Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture.

This is how Richard Dyer described it:

"The music pulsed through his entire body and emerged through his hands and arms and eyes. Every move he made radiated joy and purpose and his eyes positively shone. He visibly loved every moment of the music as he enabled and allowed it to tell its story, and that’s what made the musicians and the small staff audience love it too. No film depicting Napoleon’s defeat at the Battle of Borodino that I have seen summoned as much blood, thunder, and patriotic thrill as this simple but knowledgeable and deeply-felt run-through."

BPYO violinist Greta Myiatieva connects with a Peruvian counterpart

On their own, without the enthusiastic leadership of the Peruvian kids, our orchestra would certainly not have been able to give such a rousing performance at sight, but led by the kids from the barrios of Lima - eager, as they were, to share their mastery of the piece - everyone rose to the glorious occasion. Differences of age and social status, as well as barriers of language and musical experience, simply melted away.

Here is BPYO violinist, Arayanna Carr-Mall's description of the event:

"My stand-partner, Estrella, was a sweet 13-year-old Peruvian girl who spoke no English. Since I spoke no Spanish, at first we felt lost and smiled awkwardly at each other, waving since it was one of the only international gestures we shared. Suddenly, Estrella grinned with an idea, pulling out her phone and using a Spanish-English translation app to type "Hi! How old are you?". From there our conversation took off and I learned that she had a best friend that lived in Tampa, Florida, while she learned that I lived in Massachusetts which was much colder. Our conversation turned to the piece that her orchestra had been working on for weeks, the 1812 Overture by Tchaikovsky, which BPYO was about to sight-read. "This piece looks hard," I typed, gesturing to the music. She typed back, "It is. Good luck!". Although my sight-reading was egregious, at every rest, she would give me a thumbs up and exclaim "Bueno!"

What a perfect beginning! On our very first morning, the usual sense of superiority of the North Americans, from their fine schools and privileged backgrounds, were being inspired and “led” by their South American counterparts, from truly deprived backgrounds. Can anything else but music create such a transformation?

Then we played the first movement of the Hindemith. By now all the inhibitions had broken down, so the Peruvian kids joined in as best they could, egged on by their partners from North America.

Here is Rodion, our Russian oboe player:

"After a whole day on an airplane, it was a great joy to be around and play alongside kids who were so serious and passionate about music-making. It was an incredibly moving experience. I was the first oboist to walk into the rehearsal hall, so I got a chance to greet almost every single kid in the woodwind section. It felt super heartwarming to get to know all of them and know how happy they are to play with us. My limited Spanish vocabulary didn’t discourage me at all, but only enhanced this experience, it was all about music making and sharing all the knowledge we were able to offer, we were speaking a true language of music. Every young oboist got to try our oboes and reeds and in return we had a chance to try theirs. Some pieces we even played on each other’s horns. There was plenty of laughter from the silly mistakes we were all making and we just had so much fun! While playing Hindemith, our oboe section literally couldn’t stop laughing. The first movement is not an easy movement to sight read, but these kids tried and tried, as hard as they could! Every time the 16-notes tonguing passage appeared everybody would just burst into laughter, that kind of uncontrollable laugh when you also start crying. After we finished playing, we exchanged our contact information and took some great pictures. I’m positive this is not the last time we'll see them. I have a feeling we’ll hear from them again very, very soon."

After that we all played Stars and Stripes Forever. I explained that though that was the name of the American Flag, they shouldn’t think that by playing it we wanted to flaunt our American patriotism. Far from it – indeed, the BPYO is a veritable melting pot of nationalities. I explained that the flag 'Stars and Stripes' does represent certain values: open-heartedness, generosity, energy, liberty, forward thinking, justice, courage, curiosity and love – but these aren’t American values, they are human values and we want to encourage them everywhere.

Through our translator for the morning, Elmer Churampi, our star Peruvian trumpeter, home amongst his musical friends and former teachers for the first time since he was a kid, everyone in that room understood the message. The music unleashed all those qualities in every musician, equally among the Peruvian and the Boston kids, as they threw themselves whole-heartedly into the performance. I don’t think the performance I heard on the Esplanade from the Boston Pops on July 4th, a few days after I got back, had any more zest and fervor. They were all true “Americans” at that moment and they were expressing more energy and joy than most of them had probably ever expressed.

And equally, every one of those children in that room could understand the story of the incredibly brave Finnish resistance against Russian oppression that is played out in Sibelius’ Finlandia. When I asked everyone to sing the famous hymn of freedom, which has become like a second National Anthem for the Finnish people, I dare say more than a few goose-bumps were raised. Certainly mine were. It all flowed like barrels going over a waterfall.

The two maestros.

Here is Dyer again:

"The Telefonica corporation in Spain sponsored this event – and the tiny audience in the Teatro Municipal rehearsal room was augmented by one in Spain, watching through a satellite relay. Telefonica should feel justly proud of this particular example of its philanthropy. A founding patron of this orchestra of eager youngsters is the most prominent Peruvian opera singer of his generation, Juan Diego Florez. Zander remarked that the one thing these assembled musicians had in common is music, and that seemed more than enough. It was wonderful to watch the faces of the stand partners from north and south America as they played together, and at one point Zander proclaimed, “Stand up and hug your stand partner.” The encounter was as much a matter of smiles, glances, and shared endeavor as it was of words. And as the morning went on Zander presented more and more invitations for a wider range of hugs – and one young Peruvian woman emailed him to tell him the hugs were the best part of her day."

BPYO and Sinfonia por el Peru perform Stars and Stripes Forever

BPYO and Sinfonia por el Peru perform Stars and Stripes Forever

Should I have worried that the spontaneous confusion would look bad to the Telefonica sponsors back in Spain? Of course not! The event far surpassed their expectations, because what they could see through the video-feed was a deep connection and joy shared between young people from totally different cultures, social and financial strata. All barriers and assumptions about worth and status, even language, were swept away by the simple act of making music together.

Their patron, the famous tenor Juan Diego Florez wrote:

"Dear Maestro Zander and all the team BPYO, Thank you very much for having touched and inspired the kids of the Sinfonia por el Peru Youth Orchestra. They will never forget that moment in their lives. I have received many videos documenting this beautiful experience. Maestro Zander thanks for what you do to make this world a better place."

– Juan Diego Florez

Thank you, Juan Diego and thank you, Telefonica! We had the best time. It was only the first morning of our tour and already a bunch American youngsters in a strange land - many of them away from home for the first time – had forgotten their exhaustion and their home-sickness and given their hearts (and email addresses) to a hundred instant new friends from another world. What a roomful of love! What a whirlwind of energy! Everyone in that room had discovered, some of them for the first time in their lives, a deep new bond to share through music. Shining eyes were everywhere!

Listen and watch the whole group play Nimrod together at the end of the morning – with all the Peruvians sight reading, followed by many, many hugs:

Here is Arayana once more:

"I felt extremely touched and realized these moments of connection with the South American people were what I, and hopefully people like Estrella, would remember when we thought of our separate countries in the future. I realized this was the reason we were on this tour – to spend 13 days repairing the bridges that Trump and modern politics had broken recently. This realization that we were actually making a real impression and change, the realization that this tour was my chance to contribute to the positivity and peace internationally, made each bow I played more energetic, each crescendo in our music more drastic, and each smile more enthusiastic and genuine."

THE CONCERTS

BPYO performs in Buenos Aires, Argentina

I would love to describe all the concerts that we gave, but it would take too much time and space. Suffice it to say that every concert was given in a world-class concert venue – some old-fashioned opera houses, with long traditions, like Rosario and Cordoba in Argentina, or Montevideo in Uruguay:

BPYO receives a standing ovation in Montevideo, Uruguay

Some were spectacular modern venues with brilliant acoustics:

BPYO in Buenos Aires, Argentina

All of these halls were sold out and every concert ended with a wildly enthusiastic standing ovation – some with more than one standing ovation! The audiences poured out their collective love and appreciation with an enthusiasm and warmth that was eye-opening to our kids. We had received standing ovations before in Symphony Hall in Boston, in Carnegie Hall in New York, and at the Philharmonie in Berlin – indeed everywhere we had gone – but the warmth of the South Americans was a new experience for our kids, though a fond memory for those of us who had travelled in South America before. It’s as if these people see music – classical music – as a matter of life and death.

“We brightened the days, and even lives, of so many people. We touched their lives in ways that couldn’t be possible without music-making. I was surprised to realize that these beautiful people also touched my life in ways I could not predict. Those people, concerts, side-by-sides, and experiences gave me hope for a future in music, and in life.”

– Hannah Culbreth, BPYO Horn Player

It may come as a surprise to hear that our concerts were sold–out. How is that possible with a youth orchestra? But this wasn’t a youth orchestra tour - it was an international tour of an orchestra that just happened to consist of young people from 12 to 21 years of age. In each city the concert was presented by the top concert agency and tickets were sold at regular prices. It was the first tour, of the twenty–two that I have taken, where huge amounts of our time and energy did not need to be spent in trying to persuade people to come to a youth orchestra concert. They were sold out anyway! That meant that every spare moment could be spent connecting with young people, through all the many youth music programs in the cities we visited.

This blog will include one unedited performance of each work of our repertoire, though all the performances will be posted eventually on the BPYO website. Generally speaking, the performances got better as a result of the rehearsals along the way, so most of the performances come from Buenos Aires and Montevideo.

However there is one exception. The performance of Finlandia we gave in Symphony Hall in Boston earlier in the year was recorded by the same engineers who recorded the grammy-winning Shostakovich Symphonies by Andris Nelsons and the Boston Symphony. They also made the stunning recording of the BPYO performance of Mahler 6th that has since been released as a commercial CD!

The combination of Symphony Hall's acoustics and the superlative recording technology simply cannot be matched by the recording teams on tour, so below, to begin, is that performance from Symphony Hall.

Finlandia in Symphony Hall:

For comparison, here is also the final performance we gave of Finlandia in the concert in Montevideo, which has possibly greater flexibility and suppleness, especially in the great hymn of freedom. By this stage in the tour, the orchestra was playing this work “by heart”.

Finlandia in Montevideo:

Elmer

Elmer Churampi, BPYO Trumpet Soloist, warming up before the concert.

The big news in Peru, indeed the very reason we had decided to include Peru in our tour itinerary, was our long-term star trumpeter Elmer Churampi. Ever since we contemplated going on tour to South America, the idea of realizing Elmer’s long-held dream of returning to Lima as soloist with BPYO seemed irresistible.

Elmer began studying trumpet when he was 4 years old and joined the National Youth Orchestra when he was 8. He played the Arutiunian trumpet concerto with the National Youth Orchestra a year later at the age of 9! The son of a professional trumpeter, albeit one who earned his living largely by playing outside in the streets of Lima, rather than in its concert halls, it must have been apparent to everyone from the beginning that Elmer was a star in the making. At 13, he attended Interlochen for the summer and then stayed on at the Arts Academy, on full scholarship, to finish high school.

From there he came to New England Conservatory to study with Tom Rolfs and Ben Wright, the first and second trumpet players in the Boston Symphony, as a Freshman, the same year he joined BPYO. He was one of the winners of the BPYO concerto competition this year, but we held off having him perform at the February concerto concert, instead setting him up for his debut in Lima. We had two soloists on the tour and the presenters, Conciertos Grapa and the Peruvian Philharmonic Society, had decided to have Elmer perform in the first concert in the Auditorio Santa Ursula in the Catholic University, and In Mo Yang as the soloist for the other program, playing Sibelius' Violin Concerto in the National Concert Hall the following day.

When he heard this, Elmer expressed great disappointment. “I played in the University Hall when I was eight! All my friends and teachers are expecting me to be playing in the National Theater!” Most unusually, and going against all protocol, I called the concert presenter and asked if he would permit us to switch the program around for the second concert, so that we would start with Prokofiev’s 5th symphony and then follow, after the intermission, with Sibelius Violin Concerto, followed by Elmer playing the Arutiunian. There was resistance at first, but eventually it became clear that it was the best way to go, and so it was.

The Prokofiev, as it turns out, makes an excellent first half for a concert and having the two concertos back to back – one deeply serious and profound, the other brilliant and showy – turned out to be a terrific idea, especially since the concert was free, as are all the concerts in the National Theater, so the audience was full of young people and less experienced concert-goers. Moreover, with the addition of In Mo’s Pagannini solo encore and Elmer’s spectacular encore, Libertango, with the full orchestra, it was going to be a blockbuster event.

Elmer’s first performance in the University Hall was great, but for the second one, in the packed beautiful modern 1,700 seat National Concert Hall, he truly pulled out all the stops.

Below is the recording of the Arutiunian Trumpet Concerto from that night, including the prolonged applause that showed that the people of Lima were proud indeed to have their favorite son back in town.

Here is Richard Dyer (isn’t it nice to be able to read Dyer’s wonderful prose about music again?):

"The concerto is tuneful showpiece enabling the soloist to show everything he can do in the way of speed, dexterity, range, articulation, and breath control. Arutiunian was Armenian and the melodic shapes and gestures are based in Armenian traditions, although they also sound French and Hispanic, and there are touches of jazz and blues in the slow sections. Rooted in native soil, it flowers into a very cosmopolitan concerto. Churampi plays it magnificently balancing brio and subtlety.

His tone is superb at every dynamic level and there are stupefying crescendos which never become shrill or forced. The agility never becomes inarticulate: Arutiunian slips “blue” notes into his passagework and even when Churampi is going full speed ahead, he makes each of those notes colorful and telling. He is at his best in the slower, quieter music; the glory of his playing is how he can infuse a musical line with soul. His stage manner is informal and engagingly shambling; it’s as if he doesn’t quite believe what is going to emerge from his innermost self – but that’s what does happen.

Elmer plays the Arutiunian Trumpet Concerto:

Before the encore, I told the audience that Elmer had just gotten into the final three for the First Trumpet position with the Pittsburgh Symphony, an unheard of achievement for a 21 year old who still hasn’t completed his undergraduate degree!

Dyer continues:

"He was hailed as a conquering hero, so of course there was an encore – the “Libertango” by Astor Piazzola…..Tangos, like the blues, transmute pain into passion, mourning into celebration and triumph, and Churampi’s vocal phrasing and plangent tone embrace and communicate every dimension of this – melody becomes rhythm and rhythm becomes melody. No praise would be too high for Zander’s pointed leadership and the collaborative work of Churampi’s friends and colleagues in the orchestra, beginning with the muted trumpets in the orchestra that lead it off; it is a delight to watch the percussionists function as a rhythm section – they always do that, of course, but in this piece you can see it in their eyes and shoulders and swaying bodies as well as hear it."

Elmer plays Libertango:

One of the most touching moments on the tour was the acknowledgment at the concert of Elmer’s parents when I invited them and his old trumpet teacher to take a special bow.

The audience roared their approval and Elmer’s mother wiped away her flowing tears of pride and joy. It must be hard to imagine a more moving moment for them with their hearts brimming over with gratitude for all that Boston has provided for their son.

It was heartwarming indeed to have that gratitude expressed over and over again by his parents and grandparents. After the concert there was a gathering of his entire family – two sets of grandparents, aunts, uncles, his two sisters, and many life-long friends, all of them awed and thankful for the way that Elmer had kept his simple loving devotion to his family, along with his world-class ambitions and achievements.

Ben with Elmer's family

Peru's National Youth Orchestra

Whereas on the first day we had played together with the local El Sistema children from the poorest neighborhoods, on the second day we met with the government sponsored National Youth Orchestra of Peru, consisting of the best players in the country, all of whom are on a small salary – a little like Michael Tilson Thomas’s New World Symphony. This is the orchestra that Elmer had played in as a youngster and so at the outset I had him introduce us to the orchestra and several of his former coaches.

Richard Dyer described the occasion wonderfully, as usual:

“The National Youth Orchestra has 60 players on its roster, but fewer than half of them were able to attend this side-by-side, which took place in more opulent surroundings than the Sinfonia por el Peru enjoys – a large, handsome, wood-panelled rehearsal room in the imposing Gran Teatro Nacional which opened in 2012.

Zander was having a very good morning. I’ve been attending his concerts for more than 40 years, and over the last decade I’ve spent a fair amount of time watching him rehearse, especially during tours. But he had really entered wizard mode on Sunday and put on his singing robes – he was so fired up he inspired everyone in the room.

After hearing a couple of run-throughs of Sousa’s “The Stars & Stripes Forever” – a tour encore – I had been tying to find a way to suggest to him, subtly, that it might prove helpful to rehearse this piece, which no organization actually rehearses very often because “everybody knows it already.”

It turned out that Zander was way ahead of me, and he really tore into the Sousa’s march Sunday making suggestions about phrasing, articulation, dynamics, tempos, tone coloring and quality, nuance, detail and everything else that makes all the difference. The result was a transformed experience both for the players and the listeners. A lesson in the importance of not taking anything for granted.

Then he went on to work through Tchaikovsky’s fantasy-overture “Romeo and Juliet,” a work he adores and returns to repeatedly in his conducting classes. In one sense there was no point in spending more than an hour working on a piece that neither orchestra is scheduled to perform in public. In another sense, there was every point. Zander feels that this is a perfect piece for young players; it is about their lives, and rehearsing the piece gives the players the chance to explore their feelings and experiences and apply what they have learned to the music. At one point he asked the players point-blank how old Juliet was supposed to be; none of the guesses I heard was correct. She is 14, still on the edge between innocence and experience. As he worked on a passage depicting Juliet’s hesitancies and awakening feelings, he stopped in horror. “No, no NO!,” he exclaimed. “That’s at least 17!” and the musicians howled with laughter.

BPYO and the National Youth Orchestra of Peru performing Romeo and Juliet

He did begin by observing that music cannot tell a story; it can only express emotions. But soon he was stopping to ask – what happens in this phrase? “This is where Romeo sees Juliet for the first time.” A timpani stroke signals the moment Romeo’s dagger plunges into his heart. But Zander was right when he said music teaches us to recognize and understand our own emotions. He also promoted his own convincing theory that the love music, and the violently contrasted family-conflict music, interact more powerfully (and ironically) when they are played at exactly the same tempo.

At the end of the class, Zander decided to stop working on small sections and play the whole piece through. By the end of this short piece I have known most of my life, I was exhausted and so were Zander and the players who had clearly given their all, drawing the passion and pain and rapture out of Tchaikovsky’s music by pouring all of their own into playing it.”

Dyer is right, I was fired up that day. I always am when I work on Romeo and Juliet with a youth orchestra. Players at that age seem to connect more viscerally than adults with the deep emotions explored in that terrible tragedy. I spoke unabashedly about the sexual feelings of the young lovers, which is expressed in the music and sure enough, when the great love theme reached its glorious climax, with all the strings playing full out with the throbbing winds, it tore at our heart-strings that morning as it perhaps only can with young players. At the final timpani roar I was astonished by the playing of the Peruvian timpanist who seemed to have no inhibitions or restraint – just like the terrible tragedy he was depicting.

"In the second side-by-side in Lima, I switched off playing timpani in Romeo and Juliet with the Peruvian timpanist, who by the end, played the whole piece because I was so enthralled in watching him play. His energy in playing was so different from any other player I had seen, and it made me rethink the timpani."

– Leigh Wilson, BPYO Percussionist

Franck, Hindemith, and Prokofiev

Richard Dyer describes the long process that led up to our final performance in Cordoba of Cesar Frank's D Minor Symphony. He had attended all the rehearsals in Boston, including the very first reading, and watched the unfolding of a process of interpretation:

"This was a performance about almost imperceptible transition. Each theme or episode emerged from within the one before, while simultaneously generating the next. It built to an overwhelming climax, which Franck created by assembling all of the main melodies and combining them in triumph.

No praise would be too high for the BPYO players, who entered whole-heartedly into the process of developing this performance of a work, which is itself about the process of development. The performance was powerful, passionate and, yes, sexy, and the audience went wild; afterwards Zander was careful to give solo bows to individuals and entire sections. Andrew Van de Paardt played the prominent English horn solo in the middle movement with beautiful tone and with a haunting heartfelt emotion."Cesar Franck's D Minor Symphony: (If you don’t have time right now to hear the whole performance of this rarely played masterpiece, perhaps you would just click here to listen to Andrew’s gorgeous English Horn solo from the second movement).

"...the flute of Carlos Aguilar can organize a spray of notes into patterns that are meaningful as well as decorative; he can make neatness, pinpoint intonation, and accuracy feel like a form of eloquence."

The entire performance of the Hindemith:

Prokofiev's 5th Symphony:

Here is Richard Dyer’s illuminating commentary on the symphony Prokofiev composed in 1944, as the end of WWII was near.

"Prokofiev, along with other leading artists, worked in relative safety at Ivanovo, a retreat the Soviet composers’ union had established outside of Moscow – Shostakovich, Khachaturian and Kabalevsky were also there. Michael Steinberg’s essay on the symphony points out that Prokofiev composed on music paper from the E. C. Schirmer music store and publishing company in Boston. BSO music director Serge Koussevitzky sent the paper to his old friend Prokofiev because conditions in Russia during the war were so difficult, and supplies so limited.

Prokofiev conducted the triumphant premiere in Moscow in 1945 and Koussevitzky gave the American premiere that same season in Boston – and made the first (superb) recording. It is not entirely possible to hear this work as a war symphony, however, certainly not in the way that three of his piano sonatas are war sonatas. For one thing the score incorporates themes and music that Prokofiev had composed years before the war.

And the tone of the symphony is sometimes harsh and aggressive, but it is not despairing – the Normandy invasion had occurred and the end was in sight. The symphony does depict struggle but we know what is going to win in the end. In the context of this tour it is possible to say that the struggle is between the art of possibility and the “downward spiral.” Prokofiev’s melodies do not yearn; instead they are far-flung and celebratory, even ecstatic - they stretch across an extraordinary range of pitches – no one could sing or hum these melodies. Set against them are hostile, even sneering, violin passages that tumble downward and end in a snarl, or a series of repeated notes. Repeated notes go nowhere; melodies span the skies.

This piece calls for virtuoso playing in the orchestra, and that’s what it gets from the BPYO; even the shortest solo passages are telling – the snare drum is heard in repeated tattoos, and as played by percussionist Neal McNulty they do remind us that menace is never far away."

Here is the BPYO performing Prokofiev during the tour. We are also including the performance from earlier in the year in Boston's acoustically perfect Symphony Hall:

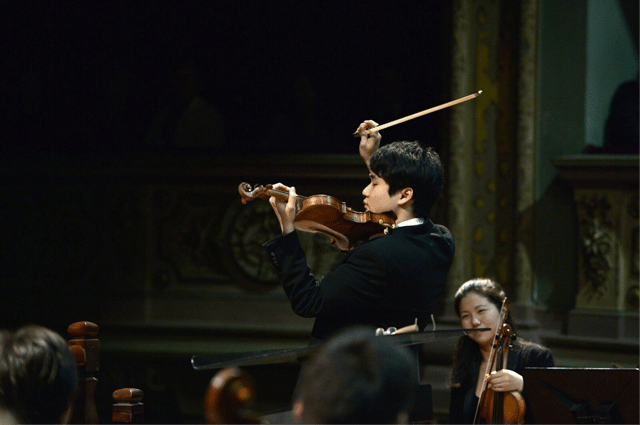

In Mo Yang

Our other soloist on the tour, was the extraordinary In Mo Yang – a twenty-one year old Korean with a starry future. In Mo won the hearts and the admiration of every single person on the tour and everyone in the audience, with his impeccable and patrician playing of the Sibelius Violin Concerto and his gob-smacking encores.

In Mo Yang, Violin Soloist, in concert with BPYO

In Mo Yang, Violin Soloist, in concert with BPYOHere is Richard Dyer on our soloist:

"Born in Korea in 1995, In Mo Yang has been earning prizes and winning competitions since he became old enough to participate in them. Most recently he won the Paganini Competition in Genoa, Italy – the first time in the last 10 years that the jury has bestowed a first prize. More significant than his list of prizes is the fact that he does not perform like a competition winner – there is nothing superficial and glitzy about him and he does nothing to “sell’’ the music to the audience beyond generously sharing the inner life of the music, and his own inner life with it. Most competition winners perform in-your-face; InMo Yang invites you to come to him – he draws you in and invites you to share his sense of the music, even if the music is a daredevil piece like Paganini’s 24th Caprice, it does have an inner life.

In Mo Yang has great beauty of tone that isn’t merely about itself – it is a tool of expression in his infinitely refined, elegant and subtle manner of playing. His interpretation may not have conveyed every untamed, wild, keening and “bardic” aspect of the Sibelius concerto, but in its own way the performance was infinitely compelling in its detail and sensitivity and poetry. His technique is both unobtrusive and totally commanding. The finale contains strings of double notes that require extreme virtuoso abilities, but In Mo Yang did not use them to show off – instead he made them sound like music that is so exuberant that it sweeps extra notes into the whirlwind. Zander and the orchestra were exceptionally alert to what InMo Yang was doing while also creating the unusual sound world of this concerto which depicts a complex natural landscape, majestic, awe-inspiring harmonious, full of bizarre sounds and happenings, and threatening in its complete indifference to what humans think about it."

Sibelius Violin Concerto:

Dyer continues:

"In Mo Yang’s encore was the Paganini 24th Caprice - a set of variations that have inspired countless other sets of variations by Liszt, Brahms, Lutoslawski and other composers. Earlier in the day he had given a master class for some members of the Sinfonia por el Peru, and at the end Mark Churchill had asked him if he would play another “little something.” A little something was not what the young violinists wanted to hear – they asked for the Paganini. InMo Yang hesitated for a bit – it was still morning and he hadn't practiced yet. But then he played it. By the evening concert he was firing on all cylinders – it was dazzling and thrilling, oh yes; the speed and accuracy were breathtaking, but so were the subtlety, imagination and command he brought to every variation. Bravo."

In Mo's encores (Paganini Caprices #13 & 24):

You now have been able to hear all the pieces we took on tour, except for the two orchestral encores, which I will leave for the very end.

A Major Disruption

Before I go on to tell about some other memorable experiences, I want to touch briefly on the only disruptive experience on the tour. It was the one thing that every tour director hopes will never happen and which had never happened on any of the 22 previous tours that I have led. We had to send someone home, actually two people.

Before embarking on the tour, we had a meeting with the entire group in which I laid out the philosophy that underlies and informs the BPYO life on tour.

We call each BPYO tour a "Tour of Possibility". In that approach, respect for each other, for people we meet, and for the whole, is a given. We have a vision and we have rules. If a rule is broken, we have to find some other recourse than sending someone home, because in an orchestra we need every single player. From this approach has sprung several practices for overcoming difficulties and provided ways of getting the group back on track, when things go astray.

These have always been used as occasions to gather the group together, so that we can deepen the commitment and learn something of value. There had never been a need to punish anyone, let alone to send anyone home. Discipline has never been an issue in BPYO, as young people, joined together by their passion for music, the demands of the repertoire, the opportunities that they are being offered, and the chance to see the world – together with other like-minded souls – is usually enough to keep everyone firmly on track.

However, there was one thing that I always put right up front before we set out. Drugs of any kind are unacceptable. It is stated in the Tour Agreement that everyone signs before we depart: "You agree that under NO circumstances and at no time will you use, or carry drugs." I emphasize that anyone who breaks this rule automatically forfeits his or her relationship to BPYO.” Nothing could be clearer.

One of our young musicians flouted that rule. He brought LSD on tour and sold some to one of the other members. It is not clear whether the other member actually used the drug, but she admitted to buying it.

It was not hard to decide that our young musician would go home immediately at his parents’ expense. It was more difficult to decide about the other member, because at first she protested her innocence. But once it was established that she had bought the drug, she too was sent home.

The loss to the orchestra of these two crucial players meant that the remaining members of their sections had to dig in extra deep to fill the sound, and since one was a wind player, that meant that a local player had to be found in each town who could perform the extremely demanding repertoire without rehearsal.

The orchestra pulled together magnificently. Morale was restored as soon as it was clear to everyone that we were as good as our word. It gave me a chance to speak to the orchestra from a place of both sadness and resolve and many spoke of having learned an important lesson. The roommate of the offender came to me to say that he now realized what I had meant when I had given out the assignment to "Take Responsibility for the Whole”. Had he thought it out, he said, he would have come forward to tell us about what was going on, because, of course he knew.

I got a letter from the offender, which I will print in full:

"Dear Mr. Zander,

I would like to sincerely apologize for what I did on tour this year. In taking drugs to Peru, I explicitly violated the terms of conduct and for that I am deeply sorry. Even though I meant no harm toward the orchestra, I can see that my actions could have caused some very negative consequences for people other than myself and I regret risking the integrity of the tour because of what I chose to do. Working with the BPYO has been an amazing learning experience, and through the orchestra, I have been able to be a part of many great experiences. My decision to disrespect you and the orchestra in the way that I did was one made without thinking and I am deeply saddened to have damaged my relationship with the orchestra. Thanks for all you have done for me in the past. I hope that I can do my part to reestablish good terms with you and the rest of the BPYO.

Nathaniel"

We have a practice in BPYO: When you make a mistake, you throw your hands in the air and say, with joy and confidence, “How Fascinating!”

This was clearly a huge “How Fascinating!” – not only for the young musician but for the other members of the orchestra, too. Everyone was brought face to face with the damage that can be done by “not thinking about consequences".

In the end, I do not regret the event, painful though it was for all of us. Everyone learned something important from it. Nor do I consider that this young man has irretrievably damaged his relationship with the orchestra. His apology, so obviously sincere, makes clear that he has learned a life lesson.

"...between many marching band, symphonic band, and orchestra trips, not once have I seen something as severe as this year's drug issue handled as maturely and effectively as it was by you [Mr. Zander], as well as my fellow musicians. Seeing an orchestra of this age group remain 100% on the correct track after an issue of that severity, is unheard of, and I'm very appreciative of you and my fellow musicians for making it an unbelievably amazing tour despite the incident."

– Mark Macha (BPYO Trumpet)

The Blue Whale

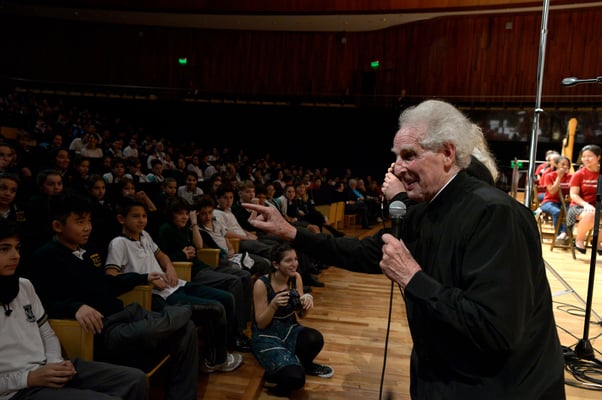

Ben Zander during a children's concert in Buenos Aires, Argentina

One of the events that I will always remember was the children’s concert in the big hall – the "Blue Whale" in the Kirchner Cultural Center - in Buenos Aires, a brand new concert hall built inside a renovated postal complex. There were almost 1,000 school children – the youngest was 7 and the oldest 13 – who sat, fully engaged, for close to one and a half hours. Most of them were hearing a symphony orchestra for the first time and I am sure they will never forget it, and nor will we! I don’t think I have ever had so much fun in a concert in my life.

My translator, Miguel Rausch, was brilliantly charismatic and between the two of us, we managed to keep up a high-energy, sometimes hilarious, banter and the kids seemed to love every minute.

Why wouldn’t they? They were hearing a fabulous orchestra, consisting of other kids, playing great music with passion and fire, in a world-class concert hall!

During Carlos Aguilar’s solo performance, you could have heard a pin drop.

Here is Richard Dyer’s comment:

"The BPYO’s remarkable flutist Carlos Aguilar earned a rock-star reception for his performance of a sultry tango by Piazzolla, Oblivion. He instinctively understands the subtle tango rhythms that no one, not even Piazzolla, could actually notate any more than Chopin could notate the elusive rhythm of a mazurka. From his flute Aguilar can summon infinite variety of dynamics and colors, bend notes downwards, flutter a tone, make an octave leap to a perfectly perched pianissimo. The strings surrounded this with swooning portamentos, and the crowd of kids went wild."

They went wild for the other pieces too: Finlandia, the Finale of Hindemith's Symphonic Metamorphosis and Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet.

Fortunately, through my effervescent translator, I could get the story of the Tchaikovsky over to the children and a broad-stroke explanation of how the music depicts the drama. When the orchestra unleashed an almost terrifyingly intense performance of the second half of the Tchaikovsky, it was obvious from the wild applause at the end that it had a profound effect on that large crowd of very young children. When I turned around, I saw a young girl of about 13 in the front row, wiping away tears. Thank goodness we had had that time together with the National Youth Orchestra in Peru for that careful rehearsal on the Tchaikovsky!

One mishap at that concert turned into a magnificent success of a strange kind. A shortness of rehearsal and a momentary lapse of planning, led to a snafu in one of the performances. Fortunately Richard Dyer was there to capture it and provide a deeper insight:

"Elmer Churampi, the BPYO’s star trumpeter, had left the tour to fulfill responsibilities back home in the U. S., so Zander had asked talented trumpeter Mark Macha if he would play the Arutiunian Trumpet Concerto. Macha had performed it before – but that was 5 years ago. And now he found himself onstage to perform it again after maybe 10 minutes of rehearsal with the orchestra. There were some frantic moments because of a large cut and a page missing from his music, but frankly this was one of the most stunning displays of courage under fire I have ever witnessed and heard. The fiercest technical passages were under control and so was his sense of the music; he left no room for doubt that under more normal circumstances he could play the whole thing with uncommon flair and command. Macha is a musician to the core, and under the most terrifying conditions he produced credible and creditable music. Bravo."

The kids in the audience, who obviously were not familiar with the Arutiunian trumpet concerto and didn’t realize anything was amiss, heard the passionate and accomplished music making and responded with a prolonged roar of approval and appreciation. It is so important for us musicians to remember that it isn’t perfection that reaches people’s hearts, but rather deep feeling and passionate engagement."

What a blessing to have Richard Dyer along, one of the most discerning musical minds and greatest writers about music who understands with such empathy the human story behind every performance.

As we became more and more connected to the audience that afternoon the excitement level rose ever higher. By the time we were playing the Stars and Stripes everyone’s eyes were shining as bright as stars and at the end it was more like a crowd at a First Connection concert than a classical music event.

Dyer caught the spirit:

"Zander really was a pied piper with these children as he chatted with them, cajoled them, danced for them, and made sure they realized that attending a concert is a very good way to have a very good time. At the end he danced up the aisles of the auditorium, surrounded by children who clamored for autographs, and he beckoned the players to come along too, making for a tumultuous melee in the aisles, which made the hall staff frantic. Certainly no one was thinking about fire laws."

Watch this hilarious video of Zander signing hundreds of hands at the Buenos Aires children's concert:

"I remember asking one child in the audience after the kid’s concert in Buenos Aires if they had liked the concert. I was blown away with how quickly he and his friends exclaimed that they “absolutely loved it” and “were absolutely amazed.” These boys showed me that every person who saw or met the BPYO took something away from that experience on a scale that I could not have imagined. These outreach events were large-scale examples of each one of us 'naming ourself as a contribution' and watching the ripples!"

– Emily Chen (BPYO violinist)

The Cellos

Mark Churchill performs with the BPYO cellos in Buenos Aires, Argentina

Inbetween the concerts and outreach events, something remarkable took place. Mark Churchill, who has been my musical collaborator for the last 40+ years and has masterminded every tour, put together a program of cello ensemble music, featuring the 16 cellists of the BPYO, as well as an ensemble of Argentinian cellists – 42 of them in total.

I turn to Richard Dyer's thrilling account of the event:

"At the Boston Philharmonic, Mark Churchill has the title "Senior Advisor," which holds no hint of the many varied things that he does. One of them is supervising the sectional rehearsals of the BPYO cellists. He often begins each session by working on the literature for cello ensemble, rather than whatever orchestral pieces are in their music folders. “Cellists love to play in groups and they do it all the time,” Churchill says and he knows what he is talking about because he is a cellist himself, as well as a conductor – not to mention all of the other administrative, creative and visionary things he does. The BPYO could not function without him - and it would not have existed if he had not insisted that it should.

(Other musicians may love to play in ensembles of their own instrument, but opportunities to do so do not arrive as frequently. The composer John Harbison, who played tuba in high school, once wrote a piece for 100 tubas that was premiered at a tuba convention.)

The kind of meticulous work Churchill does with the BPYO cello section improves intonation, tone quality, and the ability of the players to listen to each other. This goes on all season in Boston, and every time the schedule on this tour and the layout of the venues made it possible, he presided over rehearsals for the Buenos Aires program. The first richly satisfying part of it belonged to the BPYO cello section which played nine pieces by diverse composers from Bach and Handel, through Casals and Villa-Lobos, to John Philip Sousa and Zequinha de Abreu – you might not know the last composer’s name, but everyone in both Americas will recognize the tune of Tico Tico.

The kind of meticulous work Churchill does with the BPYO cello section improves intonation, tone quality, and the ability of the players to listen to each other. This goes on all season in Boston, and every time the schedule on this tour and the layout of the venues made it possible, he presided over rehearsals for the Buenos Aires program. The first richly satisfying part of it belonged to the BPYO cello section which played nine pieces by diverse composers from Bach and Handel, through Casals and Villa-Lobos, to John Philip Sousa and Zequinha de Abreu – you might not know the last composer’s name, but everyone in both Americas will recognize the tune of Tico Tico.

Thanks to Churchill and the talent and goodwill of the cellists, the playing was of uncommon unanimity and equilibrium; the diverse parts voiced and balanced in proportion; the phrasing elegant, shapely and expressive; and the collective sonority was both sumptuous and flexible. Conductor and group made themselves entirely at home in each of the styles, restrained and devout in Bach, uninhibited in Sousa’s The Stars& Stripes Forever. Hearing a group of cellists take over the role of the piccolos was both hilarious and (temporarily) convincing.

The Argentine cellists who played the next part of the program under the spirited direction of Nestor Tedesco did not have the advantage of having worked together as extensively as the BPYO sixteen; they were an ad hoc ensemble, mostly comprised, apparently, of university students, some of them more advanced than others.

The Argentine cellists who played the next part of the program under the spirited direction of Nestor Tedesco did not have the advantage of having worked together as extensively as the BPYO sixteen; they were an ad hoc ensemble, mostly comprised, apparently, of university students, some of them more advanced than others.

Each group boasted a highly partisan and vocally appreciative audience – there was a lot of whooping and hollering - and the two audiences became one when all 42 cellists joined to close the program with Piazzolla’s Libertango."

BPYO cellists join with Argentine cellists in a rousing performance of Libertango

"While each of our concerts were special in some way, I think that out of all of them, the cello choir concert was my favorite. It took a lot of perseverance and determination to get past the difficult ensemble issue of having 16 cellos. As well the collective self-doubt we shared (with the exception of Mr. Churchill), piled on top with all of the orchestra work. But when considering the satisfaction, enjoyment and thrill of the concert, these problems are nothing in retrospect. Not to mention the unforgettable bonds that we all now share!"

– Zachary Fung

Connecting Through Outreach

When we have toured in the past in Europe, between rehearsals and concerts or rushing round trying to round up an audience, we were usually sight-seeing. In South America we only went on a single sightseeing expedition – to Pachacamac. Other than that one event, the rest of the time was spent rehearsing and interacting with other young musicians in side-by-sides and various musical outreach events. There is no doubt in my mind that it was this aspect of the tour that made the most lasting impression on all of us. The memories of human interactions will be forever.

Here is an example of a touching experience, with a different and more somber aspect than the children's concert in Buenos Aires.

It was a visit to an El Sistema inspired school for children from one of the poorest neighborhoods in Buenos Aires, which was started and run by cellist and conductor Nestor Tedesco (pictured on the right), who we had known when he had been a student at the New England Conservatory.

Once again music bridged the vast gulf of social opportunity and language that separated the kids from the two worlds. At first, they broke up into different instrumental groups to work with a faculty member from the school, to prepare a new instrumental arrangement of Libertango. I was amazed when I dropped in on the percussion sectional to hear a little five year-old drummer, who had clearly impressed our college-age percussionists (see for yourself in a video taken by one of our players!).

"[In the sectional] We wanted to keep playing for hours, but we had to go watch them perform, which was as much a privilege as it was an inspiration (I was extremely shocked by the ability of a 5 year-old drummer, as he had been very quiet in the classroom). Each and every one of the kids performed with passion and enthusiasm, and even looked like they were having enormous amounts of fun. Maybe we can take a page out of their book to move towards a more pure and enjoyable musical experience for everyone."

– Reed Puleo, BPYO Percussionist

Then we all came together for a joyous and wonderfully spirited hour of music making, starting with EVERYBODY singing a lusty Happy Birthday to Ilya, one of our violinists.– isn’t it amazing to think that there is actually one song that almost everyone in the world can sing and it is a song of celebration!

Their kids sang several songs acapella, followed by our shortened version of Tchaikovsky's Romeo and Juliet, complete with an introduction so they could follow the story. Did it make any difference that we didn’t have the all-important timpani or Bass Drum? Not a bit of it! The percussion players just played lustily upon the chairs! And yet I actually think it was, if possible, an even more impassioned performance than we had done the day before in the Grand Hall! I wouldn’t want you to hear a tape, but I wished you could have seen the shining eyes! Both groups then played the new arrangement of Libertango together, conducted by the arranger – a distinguished Argentinian composer. And then, to end, we played Stars and Stripes, with several of their young children coming up one after another to conduct. It was a fabulously joyful occasion. So much joy, so many hugs.

That afternoon Mark Churchill, In Mo and I were driven to a beautiful country estate for lunch hosted by Masako Hano outside the center of town, which had been visited by many luminaries such as Picasso, Aldous Huxley, Stravinsky, Manuel de Falla, Virginia Woolf, Albert Camus, and a host of others. As we drove from the center of town where we had been that morning at the school, we passed one of the most heartbreaking sights I have ever seen – the slums where the children who had been with us that morning lived. It felt like a dagger in the heart. How could those adorable, enthusiastic, open-hearted, committed children who were bursting with joy to make music together with BPYO, go home to a scene of such indescribable deprivation?

That afternoon Mark Churchill, In Mo and I were driven to a beautiful country estate for lunch hosted by Masako Hano outside the center of town, which had been visited by many luminaries such as Picasso, Aldous Huxley, Stravinsky, Manuel de Falla, Virginia Woolf, Albert Camus, and a host of others. As we drove from the center of town where we had been that morning at the school, we passed one of the most heartbreaking sights I have ever seen – the slums where the children who had been with us that morning lived. It felt like a dagger in the heart. How could those adorable, enthusiastic, open-hearted, committed children who were bursting with joy to make music together with BPYO, go home to a scene of such indescribable deprivation?

That evening we were to take the ferry to Uruguay. As we gathered at the buses to go to the port, I said to the lead driver that I wanted the group to be driven past those slums on the way to the Ferry. “Unfortunately it is too late and it is in the opposite direction!” was the reply. I rarely pull rank when we are on tour, but this time I could brook no opposition. “We are going!” I said firmly. The buses turned around and went past those slums and when we arrived at the dock, I could see on the ashen faces of our young musicians – a look I hadn’t seen before – I surmised it was part shock, part pity, part gratitude for their own good fortune. It was a sight that would undoubtedly be imprinted on the mind of every BPYO member. And it was not just the horror at seeing such poverty, it was mixed with a sense of wonder that those children could be so utterly transformed each day, for the brief hours that they were allowed into that music school. No wonder some of the best musicians in Buenos Aires are counted amongst the faculty at that school.

There are so many other memorable interactions I wish I could share with you.

I must mention one event which I didn’t witness – actually none of the adults did. It was a visit to yet another El Sistema inspired school (in Cordoba, Argentina) and an event which was entirely run by three of the chaperones and the kids themselves. For several, it seems to have been a highlight of the tour. Clearly some of our team emerged as extremely effective teachers.

BPYO musicians and young students rejoice at a successful outreach event!

"The outreach programs were unlike anything I've done before. It was like food for the soul! I've heard people say that music is The Universal Language, and that it can break nearly all cultural barriers; but never before have I personally witnessed the extremes in which music can bring people together. It was so gratifying to have a positive impact on all the students we met, and seeing the smiles on both the kids's faces and on the faces of the BPYO musicians. That, for me, was what made this tour all the more worthwhile."

– Frank John, BPYO Tuba"When I walked into the room, I was immediately surrounded by a group of children, not much different than myself. Like our orchestra, these kids were excited to play music, they had the same markings in their music as we had, and they even talked amongst themselves just the way we sometimes would. In so many ways, it was hard to believe that there was any difference at all between us, and yet, these kids came from such different backgrounds. In some ways, I suppose one could argue that these differences of privilege and resources are minor compared to our shared love of music and life itself, but it is simply a fact that without resources, it is significantly more challenging to pursue one's passions." – Katherine Tak, BPYO Violin

"For me, the most memorable outreach was the El Sistema outreach in Cordoba, Argentina. It was great to see that we could introduce such inspiration to these children through music. When it was time for us to leave, the children ran up to us, asking us for our signatures. When the first child asked me to sign their paper, I laughed, thinking to myself, what value would my signature have to these kids? I turned away the first child that ran up to me. But children continued running up to me, insisting that we give them our signatures. I found it amusing that I was giving out my signature. However, it was a realization for me. Based on how these children reacted to our presence, they had probably never seen musicians at our level. For them to play with us, side-by-side, would be like us playing side-by-side with the BSO or Vienna Philharmonic. It really put into perspective how lucky every single one us at BPYO is, to have such frequent access to great music, to have such a high standard in our music." – Sung Ho Moon

The Last Day

On the very last day we gave our final side-by-side concert with the Sodre Youth Orchestra in the foyer of the new concert hall in Montevideo, with the audience perched on staircases on several sides and a few in front on chairs. The space didn’t have bad acoustics - actually it had NO acoustics at all.

.jpg?width=640&name=1_DSC3876%20copy(1).jpg)

Side-by-side concert in the foyer of the Teatro Solis in Montevideo, Uruguay

You’d have thought that – in such an inauspicious space – the concert would be an anti-climax, especially after the spectacular tour Finale the night before in the exquisite Teatro Solis. But it wasn’t at all. There were yet more young musicians to meet, to hug and to interact with and as usual the performances were all-or-nothing affairs, because the players from both countries were so totally engaged with the music and each other.

I saw an elderly gentleman sitting in the front row of chairs during the rehearsal. Later he sat in the front row for the concert. Whenever I looked over at him there was a beatific smile on his face, as if he knew a secret that no one else knew.

I saw an elderly gentleman sitting in the front row of chairs during the rehearsal. Later he sat in the front row for the concert. Whenever I looked over at him there was a beatific smile on his face, as if he knew a secret that no one else knew.

I then saw Richard Dyer talking with him:

"I spoke with an elderly and courtly Russian gentleman who had attended all the Montevideo events – Joseph Wainkrantz, who told me he was "only" an amateur violinist, but adding that he was an amateur violinist who loves music. His single, heartfelt word for the BPYO was "miracle." In many ways it was, and is, but the word is also slightly inappropriate because it implies something beyond the natural, something supernatural, which it isn't at all. This music making is so profound because it is so richly human."

Since it was the very last concert I had planned to end by playing Elgar’s Nimrod one last time, but I was stopped in my tracks by BPYO violinist Ilya Yudkovsky (pictured on the left), who stood up at the end of the rehearsal and pleaded with me to leave them with the memory of the night before that had been the true end for the players – that wrenching occasion, at the end of each year, when we know we are playing with each other for the very last time.

Since it was the very last concert I had planned to end by playing Elgar’s Nimrod one last time, but I was stopped in my tracks by BPYO violinist Ilya Yudkovsky (pictured on the left), who stood up at the end of the rehearsal and pleaded with me to leave them with the memory of the night before that had been the true end for the players – that wrenching occasion, at the end of each year, when we know we are playing with each other for the very last time.

There were many tears shed on both sides of the footlights.

Final performance of Elgar's Nimrod on Tour:

But I am not going to end this chronicle on such an intimate and soulful note.

Let us, rather, as the baritone sings in Beethoven's Ninth, “angenehmere anstimmen und freudenvollere” – sing more pleasantly and joyfully.

It became clear to me that for many of us this tour was in part a political journey. Several members of the orchestra told me that they felt self-conscious, even embarrassed, about traveling to South America, as representatives of a country whose current leadership has been so openly antagonistic to foreigners. However, at one concert after another the wildly enthusiastic reaction to the Stars and Stripes, showed us that our audience was responding to the energy, the open-heartedness and the enthusiasm of the young people in the orchestra.

The warm embrace of the Latin people gave courage to our young Americans that the world doesn’t see us only through the eyes of our present misguided administration.

For many of them it reaffirmed their belief that an orchestra can be instrument for keeping alive America’s vision of Possibility for the world.

Let's hear again a thought from 17 yr old Arayana, our oft-quoted scribe, who expressed it most beautifully in a letter of thanks she wrote to family and friends who had supported the orchestra on her behalf:

"This tour inspired me in music and humanity. I now feel ready to tackle the politics that I shut myself away after Trump's victory – out of hopelessness and fear – because after seeing how receptive and gracious these audiences were, I know that no matter what the news says, there is still hope and possibility in each interaction. Now that I've seen the effect that music can have, and understand that a career in music is also a career in service, my motivation and inspiration in music has grown evermore and I can see a future for myself sharing music even clearer than before. I cannot thank you enough for helping me embark on this mission that has renewed my hope, inspiration, love, and curiosity in the world.

Love,

Arayana"

That sentiment is most fully expressed in the rousing music of Sousa’s Stars and Stripes. It reminds us, and others, who we are as Americans, constantly striving to keep alive the vision of equality and justice for all. Here is the BPYO performing it at the end tour.

BPYO performs "Stars and Stripes":

One more white sheet that sums it all up (from Greta, BPYO violinist):

"I haven’t seen so many stray dogs since I left Turkmenistan. I haven't seen such poverty in which thousands live, with broken windows or no windows at all. Large families sharing single room apartments on the outskirts of the city and working endless hours to put food on the table. Kids that should be in school running around chasing each other, not yet realizing their inevitable fate of remaining exactly where they are 20 years from now.

But despite it all, I haven't seen such radiant souls, as those that I had the extreme pleasure of meeting on this tour to South America. Within minutes of arriving at the outreach venues, friendships were born. Although you nudged us all, Mr. Zander, by encouraging the frequent hugging, it was really in the nature of these kids to open themselves up and let us, the foreigners, feel welcomed and comfortable in what was a new environment.

The experience in Argentina was no different. The audiences were bursting with enthusiasm which only encouraged us stronger. The concerts only got better. Most importantly, we made music with more strangers then I have ever been able to meet in such a short period of time. And even though we had only shared a few short hours with these people, it is difficult to continue calling them that. After all, how could you be strangers with someone who's whole family added you on Facebook and have continuously invited you back to their country.This trip was so much more to me than a tour. It was the educational experience that I not only craved, but needed. To show me that making music isn't only about practicing and perfecting, it's also about sharing and learning, which is a huge aspect that most of us tend to forget.I am beyond thankful for the close to 300 new friends I acquired on this trip, as well as the knowledge of culture, people, and music.What an unforgettable experience!Love,Greta"BPYO poses for a group photo in the stunning Blue Whale Concert Hall in Buenos Aires, Argentina

"My stand-partner, Estrella, was a sweet 13-year-old Peruvian girl who spoke no English. Since I spoke no Spanish, at first we felt lost and smiled awkwardly at each other, waving since it was one of the only international gestures we shared. Suddenly, Estrella grinned with an idea, pulling out her phone and using a Spanish-English translation app to type "Hi! How old are you?". From there our conversation took off and I learned that she had a best friend that lived in Tampa, Florida, while she learned that I lived in Massachusetts which was much colder. Our conversation turned to the piece that her orchestra had been working on for weeks, the 1812 Overture by Tchaikovsky, which BPYO was about to sight-read. "This piece looks hard," I typed, gesturing to the music. She typed back, "It is. Good luck!". Although my sight-reading was egregious, at every rest, she would give me a thumbs up and exclaim "Bueno!"

"My stand-partner, Estrella, was a sweet 13-year-old Peruvian girl who spoke no English. Since I spoke no Spanish, at first we felt lost and smiled awkwardly at each other, waving since it was one of the only international gestures we shared. Suddenly, Estrella grinned with an idea, pulling out her phone and using a Spanish-English translation app to type "Hi! How old are you?". From there our conversation took off and I learned that she had a best friend that lived in Tampa, Florida, while she learned that I lived in Massachusetts which was much colder. Our conversation turned to the piece that her orchestra had been working on for weeks, the 1812 Overture by Tchaikovsky, which BPYO was about to sight-read. "This piece looks hard," I typed, gesturing to the music. She typed back, "It is. Good luck!". Although my sight-reading was egregious, at every rest, she would give me a thumbs up and exclaim "Bueno!" "After a whole day on an airplane, it was a great joy to be around and play alongside kids who were so serious and passionate about music-making. It was an incredibly moving experience. I was the first oboist to walk into the rehearsal hall, so I got a chance to greet almost every single kid in the woodwind section. It felt super heartwarming to get to know all of them and know how happy they are to play with us. My limited Spanish vocabulary didn’t discourage me at all, but only enhanced this experience, it was all about music making and sharing all the knowledge we were able to offer, we were speaking a true language of music. Every young oboist got to try our oboes and reeds and in return we had a chance to try theirs. Some pieces we even played on each other’s horns. There was plenty of laughter from the silly mistakes we were all making and we just had so much fun! While playing Hindemith, our oboe section literally couldn’t stop laughing. The first movement is not an easy movement to sight read, but these kids tried and tried, as hard as they could! Every time the 16-notes tonguing passage appeared everybody would just burst into laughter, that kind of uncontrollable laugh when you also start crying. After we finished playing, we exchanged our contact information and took some great pictures. I’m positive this is not the last time we'll see them. I have a feeling we’ll hear from them again very, very soon."

"After a whole day on an airplane, it was a great joy to be around and play alongside kids who were so serious and passionate about music-making. It was an incredibly moving experience. I was the first oboist to walk into the rehearsal hall, so I got a chance to greet almost every single kid in the woodwind section. It felt super heartwarming to get to know all of them and know how happy they are to play with us. My limited Spanish vocabulary didn’t discourage me at all, but only enhanced this experience, it was all about music making and sharing all the knowledge we were able to offer, we were speaking a true language of music. Every young oboist got to try our oboes and reeds and in return we had a chance to try theirs. Some pieces we even played on each other’s horns. There was plenty of laughter from the silly mistakes we were all making and we just had so much fun! While playing Hindemith, our oboe section literally couldn’t stop laughing. The first movement is not an easy movement to sight read, but these kids tried and tried, as hard as they could! Every time the 16-notes tonguing passage appeared everybody would just burst into laughter, that kind of uncontrollable laugh when you also start crying. After we finished playing, we exchanged our contact information and took some great pictures. I’m positive this is not the last time we'll see them. I have a feeling we’ll hear from them again very, very soon." “We brightened the days, and even lives, of so many people. We touched their lives in ways that couldn’t be possible without music-making. I was surprised to realize that these beautiful people also touched my life in ways I could not predict. Those people, concerts, side-by-sides, and experiences gave me hope for a future in music, and in life.”

“We brightened the days, and even lives, of so many people. We touched their lives in ways that couldn’t be possible without music-making. I was surprised to realize that these beautiful people also touched my life in ways I could not predict. Those people, concerts, side-by-sides, and experiences gave me hope for a future in music, and in life.”

"In the second side-by-side in Lima, I switched off playing timpani in Romeo and Juliet with the Peruvian timpanist, who by the end, played the whole piece because I was so enthralled in watching him play. His energy in playing was so different from any other player I had seen, and it made me rethink the timpani."

"In the second side-by-side in Lima, I switched off playing timpani in Romeo and Juliet with the Peruvian timpanist, who by the end, played the whole piece because I was so enthralled in watching him play. His energy in playing was so different from any other player I had seen, and it made me rethink the timpani."

In Mo Yang has great beauty of tone that isn’t merely about itself – it is a tool of expression in his infinitely refined, elegant and subtle manner of playing. His interpretation may not have conveyed every untamed, wild, keening and “bardic” aspect of the Sibelius concerto, but in its own way the performance was infinitely compelling in its detail and sensitivity and poetry. His technique is both unobtrusive and totally commanding. The finale contains strings of double notes that require extreme virtuoso abilities, but In Mo Yang did not use them to show off – instead he made them sound like music that is so exuberant that it sweeps extra notes into the whirlwind. Zander and the orchestra were exceptionally alert to what InMo Yang was doing while also creating the unusual sound world of this concerto which depicts a complex natural landscape, majestic, awe-inspiring harmonious, full of bizarre sounds and happenings, and threatening in its complete indifference to what humans think about it."

In Mo Yang has great beauty of tone that isn’t merely about itself – it is a tool of expression in his infinitely refined, elegant and subtle manner of playing. His interpretation may not have conveyed every untamed, wild, keening and “bardic” aspect of the Sibelius concerto, but in its own way the performance was infinitely compelling in its detail and sensitivity and poetry. His technique is both unobtrusive and totally commanding. The finale contains strings of double notes that require extreme virtuoso abilities, but In Mo Yang did not use them to show off – instead he made them sound like music that is so exuberant that it sweeps extra notes into the whirlwind. Zander and the orchestra were exceptionally alert to what InMo Yang was doing while also creating the unusual sound world of this concerto which depicts a complex natural landscape, majestic, awe-inspiring harmonious, full of bizarre sounds and happenings, and threatening in its complete indifference to what humans think about it." "In Mo Yang’s encore was the Paganini 24th Caprice - a set of variations that have inspired countless other sets of variations by Liszt, Brahms, Lutoslawski and other composers. Earlier in the day he had given a master class for some members of the Sinfonia por el Peru, and at the end Mark Churchill had asked him if he would play another “little something.” A little something was not what the young violinists wanted to hear – they asked for the Paganini. InMo Yang hesitated for a bit – it was still morning and he hadn't practiced yet. But then he played it. By the evening concert he was firing on all cylinders – it was dazzling and thrilling, oh yes; the speed and accuracy were breathtaking, but so were the subtlety, imagination and command he brought to every variation. Bravo."

"In Mo Yang’s encore was the Paganini 24th Caprice - a set of variations that have inspired countless other sets of variations by Liszt, Brahms, Lutoslawski and other composers. Earlier in the day he had given a master class for some members of the Sinfonia por el Peru, and at the end Mark Churchill had asked him if he would play another “little something.” A little something was not what the young violinists wanted to hear – they asked for the Paganini. InMo Yang hesitated for a bit – it was still morning and he hadn't practiced yet. But then he played it. By the evening concert he was firing on all cylinders – it was dazzling and thrilling, oh yes; the speed and accuracy were breathtaking, but so were the subtlety, imagination and command he brought to every variation. Bravo." "...between many marching band, symphonic band, and orchestra trips, not once have I seen something as severe as this year's drug issue handled as maturely and effectively as it was by you [Mr. Zander], as well as my fellow musicians. Seeing an orchestra of this age group remain 100% on the correct track after an issue of that severity, is unheard of, and I'm very appreciative of you and my fellow musicians for making it an unbelievably amazing tour despite the incident."